Profile - Tom Frost / Tartan Software

“Tartan Tam” - A British Text Adventure Legend

A proud Scot from Montrose, Angus, and a true UK text adventure legend, Tom Frost’s gaming career during the 80s and 90s, saw him involved with commercial games, magazine type-ins, homegrown adventures, and he even won an adventure competition or two.

Adventuring gaming was Tom’s main hobby but it was a hobby that had its roots in his work. Tom Frost’s day job was a quality control chemist and in the early 1980s the laboratory where he was employed ran a pilot scheme which introduced him to the exciting new world of home computers.

“We were given a ZX81 with a 16K RAMpack,” Tom told Chris Hester of Adventure Coder in 1989, “plus the necessary TV set and tape recorder and were told to ‘familiarise ourselves with the computer’ using the manual and a couple of game tapes!”

The games were all of the “arcade” variety but someone mentioned that there was a completely different style of game available, where you used your brain to solve and investigate clues. Intrigued by this, Tom went out and bought one of these “text adventures”. The game was Inca Curse, which was published by Artic Computing in 1982. The level of interactivity in the game fascinated him.

“When I typed in the command KICK DOOR and got the response “Ouch!” I was well and truly hooked and I’ve never looked back since,” he recalled in a 1992 Sinclair User interview.

Tom bought the same equipment for his own use at home. He was soon wondering if he could write his own adventure games.

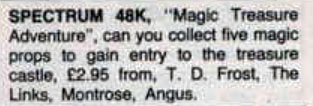

By 1984 he had upgraded to a ZX Spectrum 48K and could be spotted in the classified advertisement section of Popular Computing Weekly selling his own game the Magic Treasure Adventure. “Can you collect five magical props to gain entry to the treasure castle?” the advert asked.

By 1984 he had upgraded to a ZX Spectrum 48K and could be spotted in the classified advertisement section of Popular Computing Weekly selling his own game the Magic Treasure Adventure. “Can you collect five magical props to gain entry to the treasure castle?” the advert asked.

Tom was soon collecting treasure of his own. 1984 would end up being a very important year for his adventure gaming career.

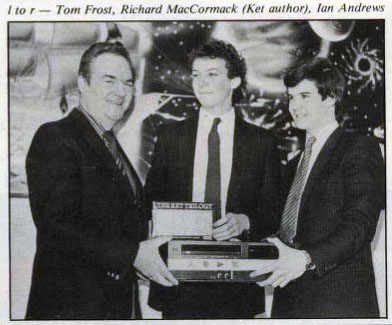

Incentive Software had launched a competition linked to their trilogy of ZX Spectrum adventure games; Mountains of Ket, The Temple of Vran, and the Final Mission. To claim the title of ‘Britain’s Best Adventurer’ players needed to finish all three parts of the trilogy with 100% scores, collecting and completing a secret message. As an added incentive, pardon the pun, the winner would also receive £400 worth of video recording equipment. That was a prize worth playing for, back then!

Prizes linked to adventure games weren’t uncommon in the 1980s. In the very same issue of Micro Adventurer, that detailed the Ket Trilogy competition, Carnell Software launched its own quest, based around their Wrath of Magra videogame. The prize was to be a brand new Flan 64K, an oddly-named British 8-bit computer system. Unfortunately the associated game was delayed multiple times and eventually only got released when Carnell was liquidated, and was subsequently rescued by Mastervision. The Flan 64K itself seemed similarly cursed, eventually launching in 1985 as the Elan Enterprise.

But a £400 video recorder or an obscure home computer system was small change compared to some of the earlier competition prizes linked to adventure games. These included a £6,000 golden sundial for Automata’s Pimania and a £10,000 prize for solving Artic Software’s Krakit. The prizes for both those games were buried beneath mounds of incredibly obtuse puzzles; well hidden and out of the reach of most of the gamers who purchased the software.

Solving The Ket Trilogy seemed a more realistic challenge, and that’s what Tom Frost set his sights on doing. Along with an article reviewing and exploring the earlier two titles in the series, Tom wrote a piece for Micro Adventurer magazine documenting the experience of attempting to solve the final game.

"Dateline: 19th September, 1984. THE DAY has arrived,” the article began. “After successfully solving all of the problems in Mountains of Ket and Temple of Vran the pre-paid copy of the third part of the Ket Trilogy is due today. Where is that postman? Computer, TV and tape-recorder are at the ready. A day off from work has been arranged as preparations are made to win the video recorder and title of Britain's Best Adventurer. Check letter-box again. Nothing! Re-check calendar. Yes, today is the 19th. Click, rattle. Dash to the front door. Small parcel on the floor. Rip open and off we go!"

"Dateline: 19th September, 1984. THE DAY has arrived,” the article began. “After successfully solving all of the problems in Mountains of Ket and Temple of Vran the pre-paid copy of the third part of the Ket Trilogy is due today. Where is that postman? Computer, TV and tape-recorder are at the ready. A day off from work has been arranged as preparations are made to win the video recorder and title of Britain's Best Adventurer. Check letter-box again. Nothing! Re-check calendar. Yes, today is the 19th. Click, rattle. Dash to the front door. Small parcel on the floor. Rip open and off we go!"

A couple of months later, Tom had completed his mission and solved the final challenge. He had his solutions verified by Incentive just before Christmas. “It makes a change for a prize to have been won, “ quipped Tom at the awards ceremony, a reference to the fact that the Pimania and Krakit cash was still unclaimed.

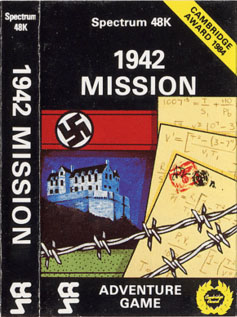

Britain’s Best Adventurer wasn’t the only award Tom won in 1984. He’d also entered the 2nd Cambridge Award Competition, run in conjunction with Sinclair User and Cases Computer Simulations. The competition was ‘intended to encourage the development of intellectually stimulating games programs written for the Sinclair computers’.

Britain’s Best Adventurer wasn’t the only award Tom won in 1984. He’d also entered the 2nd Cambridge Award Competition, run in conjunction with Sinclair User and Cases Computer Simulations. The competition was ‘intended to encourage the development of intellectually stimulating games programs written for the Sinclair computers’.

His submission, entitled 1942 Mission, missed out on the grand prize, but was one of the four ‘second-placed’ games, winning him £250 and ensuring a release of the game through CCS.

1942 Mission wouldn’t be Tom’s sole “professional” commercial release, but by now he had set up his own homegrown publishing label Tartan Software because, in his own words, “other companies refused to publish my work”.

In fairness, companies were interested. Anco Software had snapped up Tom’s next program, the multi-part Spy Trilogy, but they never released it. Undeterred, Tom put out the trilogy himself through Tartan in 1986.

In Spy Trilogy, you must make your way through a dream sequence and a training mission before taking on a more difficult real-world espionage adventure. There is a time limit for each part but you can opt to turn it off and explore the game first, without having to worry about the number of moves you have left. The game even helpfully tells you where abouts on your paper to start to draw your map. All three parts of the game feature simple colourful graphics and text, and very neat screen presentation that shows off Tom’s skills as a programmer.

In Spy Trilogy, you must make your way through a dream sequence and a training mission before taking on a more difficult real-world espionage adventure. There is a time limit for each part but you can opt to turn it off and explore the game first, without having to worry about the number of moves you have left. The game even helpfully tells you where abouts on your paper to start to draw your map. All three parts of the game feature simple colourful graphics and text, and very neat screen presentation that shows off Tom’s skills as a programmer.

Unlike many others involved in the homegrown (and indeed commercial) text adventure scene, Tom was a proper adventure programmer, doing the actual coding himself, and regarded those that used tools and aids written by others, as merely writers or designers. He originally started off producing his adventures in Sinclair BASIC, before moving on to a combination of BASIC and machine code. Fed up of writing the same code for each subsequent release, he ended up putting together his own game creation utility.

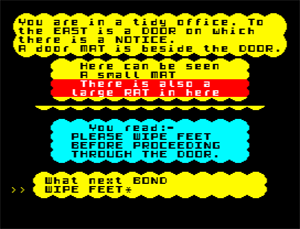

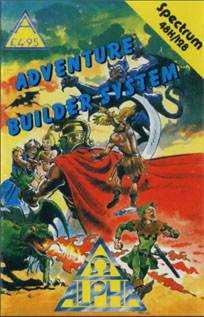

This Tartan in-house tool was called the Adventure Builder System, or ABS for short. It was made available to the general public both as a Sinclair User type-in program listing, in the June & July 1986 issues, and also in enhanced form, as a tape release with a proper manual, through Tartan Software itself.

This Tartan in-house tool was called the Adventure Builder System, or ABS for short. It was made available to the general public both as a Sinclair User type-in program listing, in the June & July 1986 issues, and also in enhanced form, as a tape release with a proper manual, through Tartan Software itself.

After seeing the success of other utilities, such as Gilsoft’s Quill, the games publisher CRL became interested in the ABS program and released it through their Alpha-Omega software label. It also got an additional outing on the Power House compilation How to Get the Most out of Your Computer.

The Adventure Builder System was a very clever program but one that was quite daunting to newcomers to programming. Prospective adventure authors had to edit the base BASIC program to add their custom information, such as messages, locations, and vocabulary. This code generation program would then compile the data into a form that would work in conjunction with machine code to produce a surprisingly fast and responsive adventure game.

The utility was ultimately a lot less user-friendly than competitors such as the Quill and Ket Trilogy publisher Incentive’s own Graphic Adventure Creator. As a result, despite retailing at half the price of its competitors, there weren’t many adventures released using the tool. The games The Golden Locket and Radiomania, published in the 1990s by Zenobi Software, the only stand out examples.

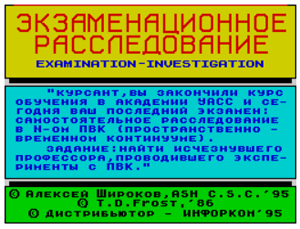

Well, the only stand out examples in the UK, that is. A whole collection of games were produced with the ABS system in Russia in the late 1990s. Games like Examination Investigation, Find Exit, Kill the President, and Ivan Tsarevich. Mentions of ABS and Tom Frost lie buried, on their loading screens and introductory pages, among the Cyrillic script, like a delightful mix of Scotch and Vodka. It would be fascinating to find out more about these adventures.

Well, the only stand out examples in the UK, that is. A whole collection of games were produced with the ABS system in Russia in the late 1990s. Games like Examination Investigation, Find Exit, Kill the President, and Ivan Tsarevich. Mentions of ABS and Tom Frost lie buried, on their loading screens and introductory pages, among the Cyrillic script, like a delightful mix of Scotch and Vodka. It would be fascinating to find out more about these adventures.

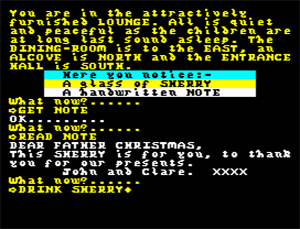

Jumping back in time and back to Scotland, Tom’s next game, A Crisis at Christmas, once again showcased his Adventure Builder System and, like the system itself, it was also printed as a type-it-in-yourself listing in the Christmas 1986 edition of Sinclair User.

Jumping back in time and back to Scotland, Tom’s next game, A Crisis at Christmas, once again showcased his Adventure Builder System and, like the system itself, it was also printed as a type-it-in-yourself listing in the Christmas 1986 edition of Sinclair User.

A simple festive tale, Crisis at Christmas gave the player the task of locating two missing presents and of making sure they’re wrapped up and under the tree ready for opening in the morning.

Although Tom had created his own adventure system, he wasn’t averse to publishing games on his Tartan label that had been made using other tools. The Quilled games of Gladys and Gerry Officer (Shipwreck, Castle Eerie, Prince of Tyndal, The Crown of Ramhotep, and The Prospector) were all well received by critics and adventure players alike.

Although Tom had created his own adventure system, he wasn’t averse to publishing games on his Tartan label that had been made using other tools. The Quilled games of Gladys and Gerry Officer (Shipwreck, Castle Eerie, Prince of Tyndal, The Crown of Ramhotep, and The Prospector) were all well received by critics and adventure players alike.

Another Quilled game, Rays, by author Audrey Meredith, didn’t go down as well with reviewers. At least, not initially. Respected adventure columnist Keith Campbell panned the game when he covered a pre-release version in Computer & Video Games magazine.

The bad review seems to have resulted in the game being partially rewritten, as the published game bares little resemblance to the one in Keith’s review. From almost zero to hero, Rays, and its planned supporting B-side games, would later be incorporated into one of Tartan Software’s most memorable releases.

Tartan Software’s Six-in-One tape was a novel twist on a compilation tape. Not only was it incredibly good value, but it was also aimed at beginner-level adventurers. It presented a collection of games, usually referred to as the Door series. Each one gradually increased in difficulty and featured plenty of help for newcomers to the genre.

Tartan Software’s Six-in-One tape was a novel twist on a compilation tape. Not only was it incredibly good value, but it was also aimed at beginner-level adventurers. It presented a collection of games, usually referred to as the Door series. Each one gradually increased in difficulty and featured plenty of help for newcomers to the genre.

It started with a simple introductory adventure (based on an earlier ABS demonstration game). The next title, Open Door, was another straightforward excursion. The previously released Crisis at Christmas slotted into the series, after being given minor tweaks and the subtitle White Door. The entertaining ABS-powered Green Door and Red Door games came next, which incorporated storylines written by Audrey Meredith, and it was her Quilled Rays game that became the Yellow Door that completed the six adventure set.

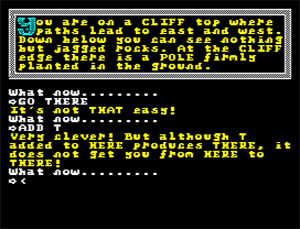

As was often the case with Tartan games, Tom delighted in filling up all the available memory with extra responses designed to cater for more obscure inputs. Although Open Door was a beginner’s adventure, Tom added some clever inputs that a more experienced, lateral-thinking adventurer might type.

As was often the case with Tartan games, Tom delighted in filling up all the available memory with extra responses designed to cater for more obscure inputs. Although Open Door was a beginner’s adventure, Tom added some clever inputs that a more experienced, lateral-thinking adventurer might type.

“[Being presented with the objective to get from HERE to THERE] ...the cynical experienced player who might be considering that such an easy adventure was a bit beneath him might be amused if he entered ADD T or even GO THERE,” Tom wrote in an Adventure Probe fanzine article.

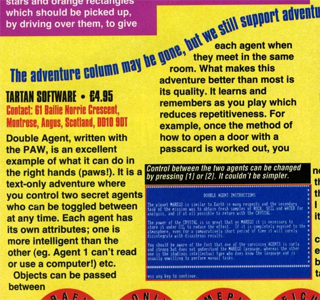

If Six-in-One was aimed at beginners, Tom’s next game Double Agent was definitely one for more experienced adventurers.

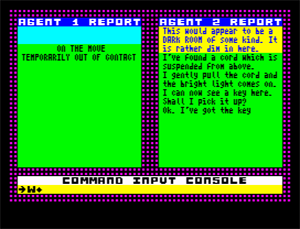

Double Agent was a game changer. A technical tour-de-force, breaking new ground in presentation and gameplay, and setting in place the style and format of the final Tartan releases to come. It was created with a custom engine, rather than the standard ABS, and the game was apparently a “nightmare” to program.

Double Agent was a game changer. A technical tour-de-force, breaking new ground in presentation and gameplay, and setting in place the style and format of the final Tartan releases to come. It was created with a custom engine, rather than the standard ABS, and the game was apparently a “nightmare” to program.

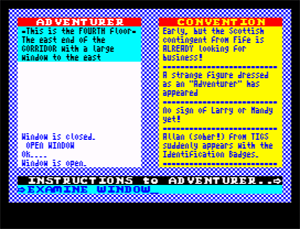

Double Agent puts you in control of two playable characters, the titular agents, who have to recover a stolen crystal from an alien planet. The top portion of the screen is divided in half, one side for each agent, and you issue commands to each one in turn. To add an extra twist to the adventure, the agents have different skills. One of the agents is more intellectual, can operate complicated machinery and read the local alien language. The other agent is better at physically demanding tasks. You need to use the skills of both agents, often working together, to make it through the adventure successfully.

Your Sinclair deemed that it was “Tartan’s best release yet”, Sinclair User called it “very original and completely absorbing”, and Crash gave it an extremely positive review with an 81% score.

Perhaps as an acknowledgement of his adventuring roots, Tom offered a £50 prize to the person who submitted the shortest solution to the game. The Double Agent adventure also came with a free bonus mini-game, Escape, on the other side of the tape. This was a more traditional ABS-powered game, filled with puns.

Tartan’s split-screen system returned in their next game, the multi-part adventure The Gordello Incident. Refining the concept and improving several technical aspects of the system, the game swapped the agents for clones (albeit clones of an agent!) who had to thwart the plans of the evil Doctor Gordello.

Tartan’s split-screen system returned in their next game, the multi-part adventure The Gordello Incident. Refining the concept and improving several technical aspects of the system, the game swapped the agents for clones (albeit clones of an agent!) who had to thwart the plans of the evil Doctor Gordello.

Each of the game’s main three parts puts a different twist on the two-character gameplay. In the first section, one of the clones is imperfect and does the opposite of what you tell it to do. In the second part, both clones respond to the same command. In the final main section, you control a single clone with the other half of the screen used to command any of the characters you encounter roaming around the game world.

In his review of the game, Mike Gerrard, of Your Sinclair, wrote: "Gordello is a fascinating adventure, and in amongst all these complications of plot, screen layout, character-switching and programming there are some clever puzzles as well. The features in the game aren't just gimmicks, they are actually part of the story and part of the problems too."

It’s no surprise then, that The Gordello Incident took a period of eighteen months to write. As well as the many technical upgrades to his system, Tom also took the time to add new features like an undo/oops command to make it more user-friendly, and introduced both an easy and a hard mode… although the easy mode was tricky enough for most players!

The game was very well-received in the press. The Games Machine awarded it a massive 93% and said that they couldn’t recommend The Gordello Incident highly enough as “it’s unique and cleverly designed.”

That clever design was all down to Tom spending hours working not just on the programming, but also on the puzzles for his games. Tom was fascinated with many possible variations of the old adventure game theme of literally or metaphorically finding a “key” to open a “door”. The content for most of his adventures came from a variety of sources “but mainly during family walks with the dog (who does NOT contribute although it may seem like it) when various ideas and concepts are thoroughly discussed.”

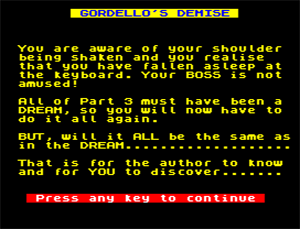

The Gordello Incident felt fresh and original, but Gordello’s Demise, the sequel and the third of Tartan’s multi-character games, felt like a retread of old ground, quite literally, as it reused the setting from part three of The Gordello Incident. It was more of a remix of the early adventure, with the same premise but lots of different solutions to the puzzles.

The Gordello Incident felt fresh and original, but Gordello’s Demise, the sequel and the third of Tartan’s multi-character games, felt like a retread of old ground, quite literally, as it reused the setting from part three of The Gordello Incident. It was more of a remix of the early adventure, with the same premise but lots of different solutions to the puzzles.

It still was an enjoyable and complete experience, and got decent reviews, but Your Sinclair’s Mike Gerrard wasn’t the only one thinking it was time “Tom Frost left his split-screen games behind and concentrated on writing a strong new storyline, rather than just twiddling with old ideas.”

Gordello’s Demise did include part three of The Gordello Incident on the other side of the tape. Indeed, Tartan’s games were always good value. They often had undocumented freebies such as a ‘golf scorecard’ program or ‘magic pairs’ game. Tom liked to test how inquisitive players were:

“On some Tartan tapes (not many I should add!)” he wrote in Adventure Probe, “I have included a short program, after the adventure, which if LOADed would inform the player that if that tape was returned to Tartan then it would be replaced, together with a free copy of the latest Tartan release! To date no return has been received! Lately, I have been including a ‘puzzle pack’ in place of the ‘return’ program, but I have yet to hear of anyone finding even that!”

Never afraid of living up to the stereotype of a canny Scot, Tom Frost had an eye for a good promotional opportunity.

His games were released on various compilation tapes, in seemingly endless combinations… the Two-in-One, The Tartan Eleven, The Tartan Seven, The Tartan Five, The Tartan Five Plus Two…. Enough to cause headaches to archivists and game collectors for years to come. There were also appearances of the Tartan games on the incredibly popular (Zenobi produced) Best of the Indies volume 1 and 2.

Tartan’s special offer coupons regularly appeared in Your Sinclair. A particularly successful promotion saw Tom Frost teaming up with John Wilson of Zenobi to give away a tape containing Tartan Software's Prince Of Tyndal and the first part of Zenobi Software's Jekyll And Hyde. The cost? Just 40p in stamps to cover the postage. It was an offer that was hard to refuse and Tom ended up sending out over 1,000 free tapes in just the first few weeks!

In the twilight years of the ZX Spectrum, magazine covertapes became a way that newcomers could sample text adventures and Tartan, like many of the homegrown publishers, took advantage of the opportunity of attracting fresh eyes to their wares. Tartan’s B-side mini-adventure Escape was a big hit on the Sinclair User covertape, making two appearances! Your Sinclair got Red Door, Double Agent and part 1 of the Gordello Incident.

In the twilight years of the ZX Spectrum, magazine covertapes became a way that newcomers could sample text adventures and Tartan, like many of the homegrown publishers, took advantage of the opportunity of attracting fresh eyes to their wares. Tartan’s B-side mini-adventure Escape was a big hit on the Sinclair User covertape, making two appearances! Your Sinclair got Red Door, Double Agent and part 1 of the Gordello Incident.

Tartan’s final game was entitled The Lost Dragon and was inspired by the events at the very first UK Adventurer’s Convention.

Tom had always been quite willing to pop south of the border for an adventuring get-together. He made an appearance in one of Mike Gerrard’s Your Sinclair articles about the Adventure Club Ltd awards bash in London, where he’d tried to convince Mike that the rapidly decreasing level of scotch at the bar was down to evaporation.

The Lost Dragon was based on another such event, which was this time organised by the readers of the Adventure Probe fanzine. The 1st Adventure Probe Convention (as it was called then) took place in a hotel in Birmingham in September 1990 and brought together readers from all across the country (and beyond) for an enjoyable all-day meet-up and awards ceremony.

In Tom’s fictitious version of events, the dragon trophy due to be presented at the end of the day was stolen by a wizard who lived on the ‘missing’ third-floor of the hotel. The adventure saw you, the player, journeying to the magical realm to try and get it back.

In Tom’s fictitious version of events, the dragon trophy due to be presented at the end of the day was stolen by a wizard who lived on the ‘missing’ third-floor of the hotel. The adventure saw you, the player, journeying to the magical realm to try and get it back.

The game, once again, utilised Tartan’s split-screen system, with the main adventure displayed on the left-hand side of the screen. On the right this time was an amusing summary of the comings and goings in the convention hall… providing the player with a useful indication of how much time they had left to complete their mission, as well as plenty of in-jokes for those in the Adventure Probe community.

The Lost Dragon was a fun game. It was also a lovely celebration of the first of many wonderful UK text adventure community events (the UK Adventurer’s Convention continued to be held annually for over twenty years) and a pretty decent final title from Tartan. Rather fittingly, there was a version of Tom’s early game Magic Treasure Adventure on the B-Side of the tape.

But although that was Tom’s last game (as far as I know), the Tartan story doesn’t end there.

After the release of the Lost Dragon for the ZX Spectrum, Tom was persuaded to port the game to the Amstrad CPC and PCW machines, which had been enjoying a bit of a resurgence in the UK text adventure scene. When doing so, he found himself, for the very first time, producing a game using somebody else’s utility…. giving him a taste of how everyone else had been doing things for years!

Tom’s chosen tool was the CP/M version of the Professional Adventure Writer, produced by the team at Gilsoft, who had released the original Quill utility that had transformed the homegrown text adventure scene many years earlier.

Writing in a letter to the Adventure Coder fanzine, his admiration for the team at Gilsoft was apparent. “The mechanics of putting the adventure together were so EASY it was untrue! [The PAW] is a true example of programming and any adventure produced using it merely basks in ITS technical excellence.”

The Lost Dragon was joined by Double Agent, which was also converted to run under CP/M+ for the Amstrad CPC128 and PCW. The split-screen features may have disappeared but Tom’s devious puzzles and clever plotting were still left intact.

The Lost Dragon was joined by Double Agent, which was also converted to run under CP/M+ for the Amstrad CPC128 and PCW. The split-screen features may have disappeared but Tom’s devious puzzles and clever plotting were still left intact.

So, what drove Tom to spend so many years (and so much of his free time) creating games?

Answering that question in an Adventure Probe fanzine article he wrote:

“...for fun and because I enjoy writing even more than playing adventures. It is certainly not for the money, fame or glory as there is not much of any of those. I very much enjoy the feedback from adventurers who have played any of Tartan’s games. Writing adventures is fun, but corresponding about them and their puzzles is also [enjoyable].”

- Profile compiled by Gareth Pitchford (August 2019)